我在中国最大的电影明星Fan Bingbing的9个月

A decade before her disappearance, the Angelina Jolie of China hired me as her tutor. I got a crash course in China’s dizzying celebrity-industrial complex.

T

he night I got a job as a fake English tutor to the very real Chinese actress Fan Bingbing, I celebrated by treating myself to a new pair of shoes at a knockoff mall in Beijing. The multilevel marketplace was where I went to buy polo shirts with inverted Ralph Lauren logos or ersatz New Era baseball caps that never quite fit. The clothes rarely lasted long, but they always helped me feel a little less homesick. Even a fake Nike tracksuit can do wonders for the soul of an expat.

T

he night I got a job as a fake English tutor to the very real Chinese actress Fan Bingbing, I celebrated by treating myself to a new pair of shoes at a knockoff mall in Beijing. The multilevel marketplace was where I went to buy polo shirts with inverted Ralph Lauren logos or ersatz New Era baseball caps that never quite fit. The clothes rarely lasted long, but they always helped me feel a little less homesick. Even a fake Nike tracksuit can do wonders for the soul of an expat.

It didn’t matter that the fresh “Adidas” shell toes I walked out in would start giving me blisters within a week, or that their non-treaded soles would cause me to slip repeatedly on greasy restaurant floors. They looked authentic enough to fool the casual observer, which made them a perfect fit for a charlatan ESL teacher.

A lifelong mumbler, I’d never been particularly good at speaking English, let alone teaching it. I’d even been fired from my former classroom job, at a college in Hunan province, for failing to “inspire the students.” I had come to China in 2005 to follow my dream of becoming a photojournalist, but by 2008, my career as a foreign correspondent had gone stagnant. I needed money, and more than that, I needed a story. The job with Bingbing, which came to me through a Chinese friend, promised both.

They called her the Angelina Jolie of China. Tall, with a slender jaw, a smooth complexion, aquiline nose, and cavernous coal-black eyes, Fan Bingbing was alluring and powerful, a fitting avatar for the material yearnings of an emergent middle class.

When I met her, Bingbing was already a massive star in China, and was just starting to find traction internationally. She was China’s de facto cultural ambassador in places like Cannes and Paris Fashion Week, and with Hollywood beckoning, she was already a sought-after spokesmodel for foreign brands entering the Chinese market. Learning English, at least enough to memorize a script, was the next step in her global conquest.

As a figurehead of the Middle Kingdom’s wishful dalliance with Hollywood hit making, Bingbing’s crossover to international superstardom seemed inevitable.

It would have been easy enough for Bingbing to locate a qualified tutor in Beijing, where thousands of American and British professionals were staking their claims in a rapidly modernizing China. But like me, she wanted a shortcut. In her case, that meant hiring a tutor in a language she never intended to learn.

As a result, for nine months I was afforded a backstage pass to China’s celebrity-industrial complex. Bingbing’s PR manager gave me permission to photograph freely while on the job, and I figured I could use my access to shoot a new “behind-the-scenes” photo essay on the Chinese entertainment industry. Little did I guess the extent to which I would become a part of the story myself.

Shortly after landing the job, I found myself on a plane from Beijing to Shandong with Bingbing’s entourage. When we arrived at her suite in the Qingdao Shangri-La, she looked down and noticed my new shoes. “Are they real?” she asked in English. “Of course,” I replied with a wink. The actress laughed and flashed a knowing smile.

T

hat was a decade ago, in the optimistic months following the Beijing Olympics, when living in China felt like being at the center of the world. The Games had been characterized as a coming-out party for the country, and the sense among some observers was that China’s market reforms would soon lead to more participatory government. A homegrown celebrity culture — and the commercialism it fed — was at the center of that momentum, and as an unofficial American liaison to the country’s most exclusive movie star, I figured I had a front-row seat on a heady moment.

T

hat was a decade ago, in the optimistic months following the Beijing Olympics, when living in China felt like being at the center of the world. The Games had been characterized as a coming-out party for the country, and the sense among some observers was that China’s market reforms would soon lead to more participatory government. A homegrown celebrity culture — and the commercialism it fed — was at the center of that momentum, and as an unofficial American liaison to the country’s most exclusive movie star, I figured I had a front-row seat on a heady moment.

Ten years on, things look very different. We know now that the Games were the start of a new push by the Communist Party to tighten its authoritarian grip on the country, which had loosened somewhat after the crackdowns of 1989. In the decade since the Olympics, China has doubled down on its use of extralegal detention and public surveillance. Millions of ethnic minority citizens are currently living in “reeducation” camps, and an ongoing media crackdown has sent novelists and journalists to prison while shifting regulatory control over commercial film and TV directly to the Communist Party Propaganda Department.

Nevertheless, the years following the Olympic Games were a good time to be Fan Bingbing. Her fame, and income, grew steadily throughout the late 2000s and early 2010s. As the actress made her first inroads into the international market, her global presence was developing in parallel to that of the Chinese film industry itself. And as a figurehead of the Middle Kingdom’s wishful dalliance with Hollywood hit making, Bingbing’s crossover to international superstardom seemed inevitable.

In 2017, Bingbing graced the cover of Time magazine, a year after she’d come in fifth on a list of the globe’s highest paid actors . But then, in 2018, she vanished. That June, a pair of duplicate contracts had leaked online, showing that she had been paid much more than she was reporting to the government for her work on Cell Phone 2, a highly anticipated Chinese dramedy. A tax investigation was launched, and in July Bingbing — who’d been omnipresent in news media for years — simply disappeared from public view.

Tall, with a slender jaw, a smooth complexion, aquiline nose, and cavernous coal-black eyes, Fan Bingbing was alluring and powerful, a fitting avatar for the material yearnings of China’s emergent middle class.

With no announcement forthcoming from the authorities, the world puzzled over her fate for three long months. Some speculated she’d fled the country. Most assumed she had been apprehended as part of an ongoing anti-corruption drive, in connection with a newly-formed government commission that was known to practice liuzhi , or “enforced disappearance.” As if to drive home a point, Fan scored “0%” last September on a state-backed research study that ranked Chinese celebrities on their level of “social responsibility.”

It was a development that would have seemed impossible even a few years earlier, when she was earning unnameable sums of money with the Party’s tacit support. At the time — riding in police escorts to holiday TV pageants hosted by China Central Television, the country’s state-run mouthpiece — the idea that she might run afoul of the authorities seemed unthinkable. It wasn’t until she disappeared that anyone realized just how far someone on her level could fall.

Of course, there had been signs along the way that not everything was aboveboard: the production expenses (including my salary) paid in thick wads of cash; the autograph-forging sessions performed by Fan’s assistants; the fully boarded Air China flights held more than an hour for our late arrival — all in a country founded on the promise of the eradication of class.

And despite her ubiquitousness, Bingbing’s public image was never entirely positive. She often sparked derision in the tabloids and condescension from consumers, many of whom saw her as inauthentic. Unlike Jackie Chan, who was universally beloved and seldom hounded by the press, Bingbing was a divisive figure whose personal life was regular fodder for negative reports of all kinds, including allegations of bribery, lip-syncing, and even prostitution. “Fan has been very successful projecting a public persona in China. But paradoxically, she has never won the public love,” Raymond Zhou, a Beijing-based film expert and critic, told me recently. “Her arrest was widely applauded in cyberspace.”

When I told people I worked for Bingbing, they inevitably asked if there was any truth to the oft-repeated rumor that her famous facial features were the result of plastic surgery. There wasn’t, though few took my word for it.

In the early years of her career, Bingbing achieved an impressive level of fame. She had a supporting role in the hit 1990s soap opera My Fair Princess , and later broke out with a lead role in Cell Phone , the highest grossing Chinese film of 2003. In 2007, the year before I came onboard, she began working closely with a new manager named Timothy Mou. Mou would not only refashion her into an international icon but also change the role of celebrity itself in a country where foreign investment was opening new doors for personal enrichment.

A notoriously bellicose entertainment executive, Mou got his start running nightclubs in Taiwan, later becoming an agent and producer of historical dramas in mainland China. After he pried Bingbing away from her contract with another management firm in 2007, Mou proved highly effective in leveraging her fame. He helped her land film and television roles, as well as the kind of brand ambassador and endorsement deals that bring in real money. Under his watch, Bingbing became the Chinese face of L’Oreal, Chopard, Moët & Chandon, Cartier, and Mercedes Benz, among others.

“In the run-up to the Olympics, multinationals were showing up in Beijing and needed to have a name and a face to help them sell products,” Jonathan Landreth, who had been the Hollywood Reporter ’s Beijing-based Asia Editor at the time, recalled. “Fan was waiting in the wings.”

“Tonight, I will show you her power,” Mou boasted to me one evening while we were on a trip to Shandong province in October 2008. We were hunkered in a tinted Buick minivan outside one of Bingbing’s obligatory state-TV concert appearances, surrounded by hundreds of college-age fans swarming to catch a glimpse of the arriving celebrities. I was, as yet, uninitiated to the celebrity-entourage lifestyle. It was dark on the road when we started sprinting toward a distant opening in the stadium, and we made the entrance just as a wall of kids closed in, their shouts and camera flashes reverberating in the stairwell as we crossed the vestibule and stormed into the arena’s underbelly. “ Wo ai ni, Bingbing! ” they shouted — “I love you, Bingbing!” By the time I left the concert, I was in a state of shock. Mou looked pleased at my reaction, chuckling as he fell into the van’s backseat, a special-edition gold-plated Nokia clutched in each hand.

An hour later, we were at a roadside seafood restaurant near Qingdao, lounging at a table littered with shellfish, steamed crab, and cash. The hallway outside our private banquet room was teeming with young waitresses elbowing for a peek through the service window. I was just starting to understand what Mou had meant by “power” when he looked up from the small mountain of bills he was counting — Bingbing’s take from the night’s performance — and, upon seeing my look of astonishment, and my raised camera, asked me in deadpan English: “Do I look like a gangster to you?”

In truth, he did. But at the time, it struck me as a joke.

O

ne of the first things Chinese students of English usually do is to decide on an English name. You can always gauge a pupil’s proclivity for self-expression by their choice. Many play it safe, naming themselves after a character from

Friends

or taking a name passed down by an older classmate. Bolder students reference their cultural role models — “Kobe” Bryant or “Steve” Jobs. (One enthusiastic graduate student I taught at Hunan University called himself “George Bush.”) English provides many students with an opportunity to express themselves in ways they wouldn’t feel comfortable doing in their native tongue, and their new name is an opportunity to create an alter ego.

O

ne of the first things Chinese students of English usually do is to decide on an English name. You can always gauge a pupil’s proclivity for self-expression by their choice. Many play it safe, naming themselves after a character from

Friends

or taking a name passed down by an older classmate. Bolder students reference their cultural role models — “Kobe” Bryant or “Steve” Jobs. (One enthusiastic graduate student I taught at Hunan University called himself “George Bush.”) English provides many students with an opportunity to express themselves in ways they wouldn’t feel comfortable doing in their native tongue, and their new name is an opportunity to create an alter ego.

Trained as an actress from childhood, Bingbing never received the language-intensive education of her millennial peers, and her English, when I first met her, was even more rudimentary than my Chinese. But Bingbing did have an English name: “Ophelia.”

Like her namesake, Bingbing was a powerful woman navigating dueling modes of female identity. Depending on the audience or product she was endorsing, Bingbing’s public image could change from objectified sex idol to wholesome girl next door. Privately, she was a cunning businesswoman, highly successful yet isolated by her fame. Warm and gracious, cold and calculating, Bingbing could be many people at once, making it difficult to spot where her personas ended and a real person began. Maybe she wasn’t sure herself.

Nevertheless, Bingbing’s sense of humor was genuine. Once, while she was filming the World War II drama East Wind, Rain, I saw tears streaming down her face. A consummate professional, Bingbing had insisted on crying real tears for the scene, which she’d managed to summon over numerous consecutive takes. After the shoot, I asked how she did it. “I think about the day my dog died,” Bingbing replied, as the sorrow on her face gave way to an impish grin. (In China, where dog meat remains a popular delicacy, people don’t generally catch feelings over the fate of canines.)

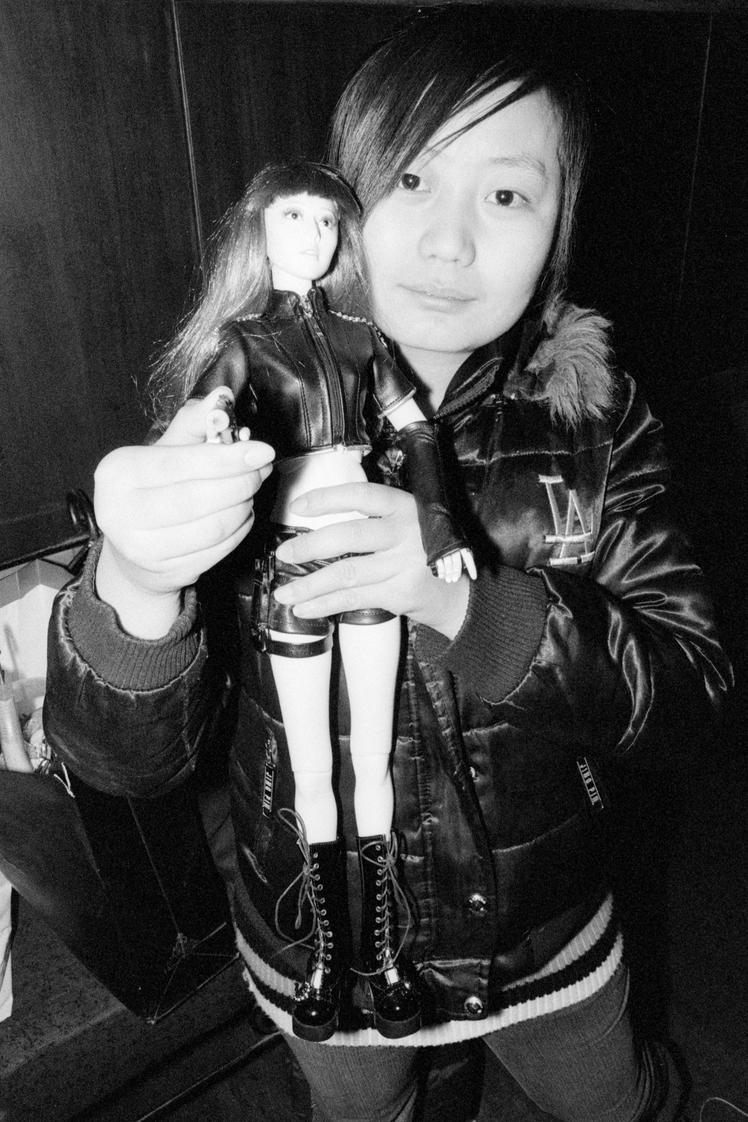

From the beginning, it was clear that we would have to start with the basics. Typical Chinese curricula tended to combine the usual family/household/barnyard vocabulary with a distinct focus on patriotic items. Along with “peacock” and “tree,” “soldier” and “flag” were deemed essential. Instead, I bought a stack of elementary-level English course books and flashcards, of the sort designed for children.

Our early classes took place at Bingbing’s offices overlooking the Dongsishitiao intersection in central Beijing. Her company, Fan’s Studio, operated out of the suite, and its employees were always busy managing the starlet’s diverse roster of business ventures, including an acting academy in Beijing, a television production house, and her expanding list of endorsement deals for everything from designer furniture to specialty cooking oils.

Our first lesson focused on adverbs: “Before,” “after,” “many,” “few.” Bingbing struggled with these concepts but could easily rattle off the names of foreign designers and luxury labels with nearly perfect locution: Dior, Ferrari, Vogue, and her favorite word, “villa.”

I didn’t know the first thing about designing a custom language curriculum for a pupil of Bingbing’s unique experience and abilities. But having bullshitted my way into the gig, I knew my only option was to establish a good rapport and project an air of confidence. If I could help her learn something, I might continue to photograph her world, while also earning 20,000 RMB, roughly $3,000 at the time, each month.

I definitely worked for it. “Laoshi, Bingbing shang ke,” Bingbing’s lead assistant, Xiao Yan, would announce over the phone in sternly efficient Mandarin. This meant that I should proceed to Bingbing’s home immediately, regardless of where I was or what I was doing. Being part of her team meant being available pretty much all the time. Often I’d receive a hurried evening call informing me that we’d be flying out early the next morning, and could I please be waiting at the airport when the rest of the entourage arrived?

I quickly learned an old lesson that was new to me: making movies isn’t as glamorous as it’s cracked up to be. When you’re on set, the vast majority of your time is spent waiting. Waiting for wardrobe, waiting for set design, waiting for lighting and camera placement, waiting for the sun to set. Shoots were often scheduled in the dead of night, which meant that I found myself up too late, sulking around the set and killing long hours waiting for Bingbing to summon me.

Her improvement was slow, but I eventually realized that simply appearing to learn English might be all she really needed. In the tabloids, I was often referred to as the star’s “foreign friend” alongside paparazzi shots showing us leaving her offices or strolling through an airport terminal. It was no accident that on the rare occasions we found time for a formal lesson, Bingbing would have us meet at the upscale Sculpting in Time café, a popular haunt of Beijing’s glitterati in the exclusive northeast corner of the city. She always made sure to cause a stir by requesting a sofa booth where we could be easily observed. Over a spread of bubble tea and french fries, she would feign interest in my review materials while blowing kisses to industry peers scattered throughout the room. Bingbing was at ease in these moments, alternating between business banter and charming retorts with effortless affability. Sitting across the table, I was her co-conspirator, the recipient of her knowing glances, a straight man to her flawless performance as a well educated cosmopolitan superstar.

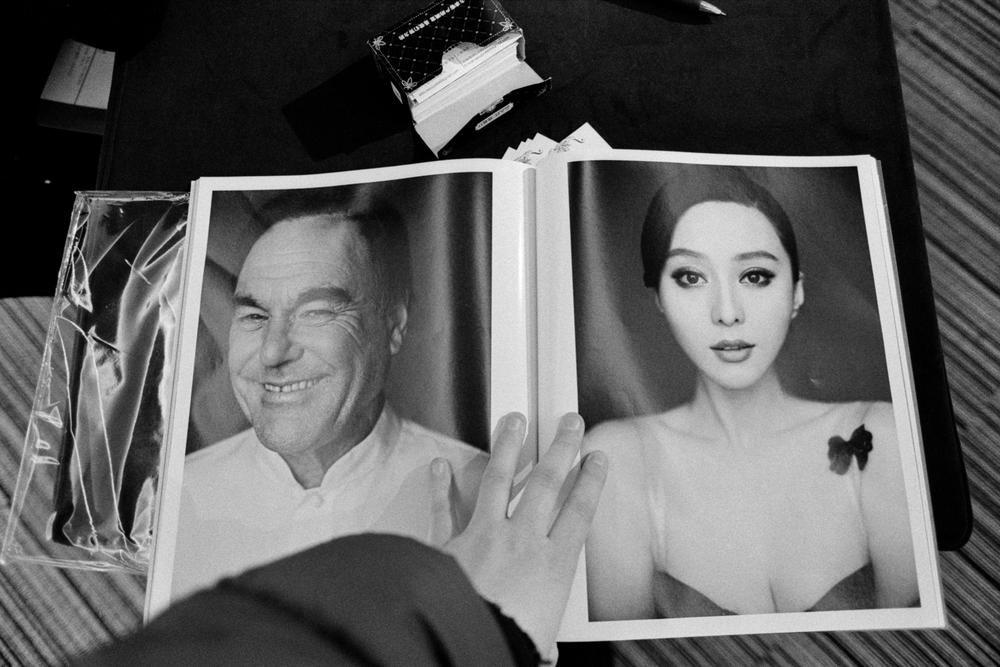

Being seen with Westerners was a key part of her strategy, which made for some uncomfortable moments. In the fall of 2008, Oliver Stone came to Beijing for a photoshoot with the local lifestyle magazine, iLook . Stone, who was originally slated to pose alone, had requested to be shot with Bingbing, whom he reportedly found “adorable.”

I was standing next to Bingbing, who was prepping at her station, when Stone waltzed in. It was his first time meeting the Chinese actress, and he strode assuredly across the room. Before Bingbing had a chance to turn around to greet him, Stone grabbed her from behind and planted a firm kiss on her cheek. She managed a forced smile, which she maintained over the uncomfortable hours to come. At one point during the shoot, I recall, I cringed as Stone tucked his face into the cradle of Bingbing’s shoulder and cavalierly sniffed her neck. (Reached for comment, a representative for Stone told me, “Nothing inappropriate happened on that photo shoot.”)

T

oward the end of the year, I followed Bingbing to Shanghai for the premiere of

Home Run

, a family drama she starred in with the great Hong Kong comedic actor Chapman To. On a free evening, Bingbing asked me to accompany her to dinner at her favorite restaurant in town. Before stepping into her chauffeured Mercedes, Mou pulled me aside. He had other obligations that night, and told me sternly: “She’s your responsibility now.”

T

oward the end of the year, I followed Bingbing to Shanghai for the premiere of

Home Run

, a family drama she starred in with the great Hong Kong comedic actor Chapman To. On a free evening, Bingbing asked me to accompany her to dinner at her favorite restaurant in town. Before stepping into her chauffeured Mercedes, Mou pulled me aside. He had other obligations that night, and told me sternly: “She’s your responsibility now.”

The restaurant, a tiny storefront eatery on Xinle Road, in the former French Concession, was simple and delicious. Its building was undergoing repairs, and stepping through a scrim of scaffolding into the neon-lit diner felt like visiting an older, more cinematic Shanghai. This was surely one of the few neighborhoods in China where a starlet could freely enjoy a meal in public, the cosmopolitan districts of Shanghai being well accustomed to the presence of rich and powerful denizens.

Halfway through a memorable spread of frog, tofu, and white radish, Bingbing gave me an informal confirmation that I had passed the probationary period of employment. “I like you,” she said. She was relaxed and in good humor, her dark eyes softer than before, her posture casual. It was the first time I felt like I was speaking to the real woman behind the mask.

“I like you, too,” I mumbled, my awkwardness met by an unassuming smile. We both laughed. After dinner, we went window-shopping and she bought me an alarm clock that projected the date and time onto the wall in a red, retro-digital display. I felt touched by her generosity, though she may have been making a sly and subtle joke about my chronic lateness.

From then on, I was treated like part of the family, or at least as a member of Bingbing’s inner circle. I accompanied her to business meetings with new clients and sat next to her at banquets with prospective investors. Clearly, I was serving as some kind of selling point. Teaching felt secondary, but I tried to keep up appearances by schooling her when and where I could. Most of our lessons took place on the road, in airport VIP lounges and shuttles, during fleeting moments of quiet in her on-set trailer, or over hurried dinners with the rest of the team.

But the truth is that Bingbing didn’t have time to learn a new language. She was wholly devoted to her two main interests, acting and making money. She excelled at both, which may hint at another reason her company was targeted last summer: As control over China’s entertainment industry drifts closer to the inner circle of the Communist Party, what room could be left for heavyweights like Fan and Mou?

I spent less than two of the nine months I was employed by Fan’s Studio in Beijing. I was living in China on an extended L-class tourist visa, so technically I was working illegally, which Bingbing’s people knew but didn’t seem to mind. Twice a month, I was handed an envelope of cash, regardless if we were at a photo shoot in Shanghai or a yachting industry awards banquet in Shenzhen.

After a few months, my suitcase started to resemble a safe. At one point, I had 70,000 RMB (then about $10,000) stashed in socks. While shooting The Last Night of Madam Chin , a soap opera produced by Fan’s Studio, I watched producers make weekly trips to the bank in pairs, returning with backpacks stuffed with money to pay the crew and the large cast of extras.

Rules, it seemed, were for other people. Once, as we reentered the mainland after a film shoot in Macau, a diligent customs agent correctly noticed that my passport was brimming with entry and exit stamps, indicating a multiyear period spent in the country. “Do you live in China?” he asked sharply, ready to investigate my obvious violation. Before I could answer, Bingbing stepped between us, gently rested her hand on his, and smiled. “He’s with me,” she intoned with her usual graceful assurance. The hard-nosed official blinked to make sure he wasn’t dreaming and waved me through, as though hypnotized.

I was treated like part of the family, or at least as a member of Bingbing’s inner circle. Clearly, I was serving as some kind of selling point.

When she felt like shopping, Bingbing would sometimes wear a disguise: a dust mask, dark glasses, a hat. Then, with her team of assistants in tow, she’d peruse the crowded fashion markets of Guangzhou or Shenzhen, discreetly trying on items, soliciting our feedback and negotiating with vendors for a lower price. Occasionally Bingbing would stumble upon a poster or cutout of herself and engage the shopkeeper in gossip about herself, gleefully polling for her own public approval rating, unseen by the fans who often swarmed her public appearances. Without betraying her identity, we’d jump in the van and head to lunch, laughing, surrounded by bags brimming with bejeweled hats and sequined sneakers, neon puffy jackets, and lensless glasses frames.

While traveling, we would always stay in five-star hotels. Commercial clients were contractually obliged to house our team in the nearest Shangri-La, a luxury hotel chain with 55 properties in mainland China. If the city was too small to have a Shangri-La, we would begrudgingly accept the next best thing. Our days consisted of shuffling between carefully orchestrated shoots and endorsement appearances, often involving multiple flights or driving with a police escort to make a concert performance in time. Coordination was left to Bingbing’s team of assistants, while I sat back and tried to squeeze in an occasional English lesson. Bingbing and I were meant to hold a formal hour-long class each day, though in practice, we rarely did. She was too overworked and exhausted.

Mostly, we just talked. Though our relationship was never anything but professional, between the shared struggle of language learning and the time we spent together on the road, we developed an easy camaraderie. Behind closed doors, we’d swap stories about our exes and shit-talk other actors. Using some of her new English vocabulary, peppered with Mandarin when necessary, Bingbing would ask about my work, tell me about her plans for buying a house in the U.S., or request my opinion about this or that magazine spread or newly cut film trailer. Often, these chats would end with Mou barging into the room and dominating the conversation. I thought it strange that someone invested in Bingbing’s career would actively disrupt what was presumably an important lesson, but he was clearly uncomfortable with the amount of time she and I were spending together. Perhaps he was afraid that if she learned too much English, she might leave him for greener pastures.

Bingbing may have been the star, but Mou — whom she called “boss” — made the decisions. He dictated which roles Bingbing would take and what products she’d endorse, sometimes even what clothes she would wear. A voluminous eater, he prided himself on choosing where we would dine (a prerogative I personally welcomed), and had preferred restaurants in each city we visited. In Guangzhou, it was an unassuming street-side eatery famous for grilled oysters and seafood stew; in Macau, it was old-school Portuguese fusion; Bangkok’s Chinatown offered the best in diaspora cuisine. Wherever we went, Mou was like a father on vacation with his family: proud, patronizing, fiercely protective, and controlling.

I’d seen this top-down Confucian management style before. Take a stroll through the commercial districts of any Chinese city and soon enough you’ll come across groups of young workers goose-stepping up and down the sidewalk outside the hair salons or restaurants that employ them, a manager barking encouragement through a bullhorn, like a drill sergeant. They call this team building. Back in Hunan, a sympathetic student had once pulled me aside to let me know I needed to “be more terrible” to my class. “Chinese students want to be told what to do,” he cautioned. “Here, the teacher is boss.” What he meant was my cool guy, throw-the-book-out, peer-to-peer teaching style was not appreciated, and that if I wanted to command my students’ respect — and avoid losing my job — I’d need to embrace the role as they saw it.

Mou was a master of this dynamic, riding our asses over tardiness one minute and treating us all to banquet meals or gifts the next. He would often call me his “good friend” between mouthfuls of shellfish; a “good teacher” when introducing me to associates. In return, I was expected to keep my mouth shut and go with the flow, and to never, ever, challenge his authority.

I began to understand what Chinese workplace hierarchy really meant.

Often this passive-aggressive workplace dynamic crossed over into the personal realm. While in Shanghai, shooting Madam Chin in the early months of 2009, I befriended a trio of female dancers who, like me, had a lot of downtime between takes. They were staying down the hall, and one night they invited me to their room to watch DVDs. It was early evening — everyone had to be up at the crack of dawn anyway — and the four of us perched on twin beds, drinking cola and munching on rice crackers and sour plums for an hour or two. I left thinking little of the mindlessly innocent flirtation.

I got a text from one of the women a day or two later and realized that she and the other two were no longer among the cohort of dancers. She said it had been nice to meet me and to let her know if I was ever in Chengdu. Mou was quick to let me know that he’d fired them. It was my fault, he chastised, for being seen hanging out in their room.

As an American, I considered this sort of treatment by an employer abusive. Sure, when we were traveling on a corporate client’s dime and I was staying in my own luxury hotel suite, I could live with it. I hadn’t given it much thought when Mou talked down to Bingbing’s personal assistant, or made her hairstylist cry. But gradually, I began to understand what Chinese workplace hierarchy really meant. And, cultural sensitivity notwithstanding, I didn’t like it.

Our friction came to a head one morning in Macau, where after a 6 a.m. wake-up call demanding I be in the lobby at 6:15 a.m., Mou made a point of lambasting me on the set of the French indie we were shooting. Stretch was Bingbing’s first English-only gig — starring opposite David Carradine, of Kill Bill fame — and I felt entitled to some credit for having prepared her for the role. “Don’t be late again,” Mou threatened sternly as I arrived, making sure Bingbing and the crew were in earshot before returning to whoever was on the other end of his Nokia.

In hindsight, what I did next was a mistake. Residual frustration from my forced awakening and a creeping hangover had nudged me toward a line that, once crossed, could not be untrod. I certainly knew that making a man lose face in front of his family, or business associates, was a cardinal sin in China. For an underling, foreigner or not, to challenge his boss in public was the ultimate gesture of disrespect. I did it anyway. “You didn’t fucking tell me we had a morning call time,” I barked.

Everyone stopped. They didn’t need to understand English to know what I’d said. Mou looked at me, hard, shook his head, and strolled away. It was one of the last times he would speak to me, other than to unravel my employment status over the coming weeks. Our final conversation came later that month, in the lobby of a Bangkok hotel, when he demanded I sign a contract relinquishing some of the rights to the photos I’d taken of Bingbing. “I am a gangster,” he intoned with the calm demeanor of a parent attempting to explain long division to a child. “And the police in Beijing don’t care what happens to foreigners, understand?”

Two days later, I was back in Beijing, safe and sound. David Carradine, on the other hand, was dead. The disputed cause of the venerated actor’s untimely demise: autoerotic asphyxiation.

I never heard from any of them again.

When the story of Bingbing’s disappearance was eventually picked up by the foreign press last September, some observers saw an innocent woman whose beauty and entrepreneurial instincts had threatened the primacy of President Xi Jinping’s ironfisted communist leadership. How could someone like Fan, who, in recent years, had started popping up in Hollywood blockbusters like X-Men: Days of Future Past and Iron Man 3 , be allowed to disappear into China’s shadowy extralegal detention system? Fan was probably the best-known Chinese starlet in Asia — and beyond — and her profile was set to expand as the relationship between Beijing and Hollywood grew closer. Nowadays, big Hollywood productions almost always consider the Chinese market from inception, prizing apolitical scripts that don’t offend, along with plotlines and performers with a proven record of success in the region. It’s one reason they keep pumping out Transformer movies.

But even if China is near and dear to Tinseltown’s heart, Beijing is not West LA, and a Chinese actress, no matter how many times she poses for photos with Will Smith or Jessica Chastain, is still beholden to the Communist Party. Given the level of Bingbing’s fame, it’s hard to interpret her treatment as anything but an example to other would-be tax evaders among China’s elite — part of Beijing’s strategy for easing the mounting public frustration over class disparity.

For China’s leaders, hyperspeed economic growth has always meant a balancing act between social stability and increased inequality. So far, the Party has wagered that a rising tide will eventually lift all boats, and as Deng Xiaoping once acknowledged, “Some people get rich first.” In the meantime, modern China has become split between extreme wealth and abject poverty — although, as my non-celebrity students would often remind me, “At least, everyone is fed.”

As a symbol of excess, Bingbing’s blatant manipulation of the system — using hidden contracts to avoid paying taxes on a $7.8 million acting job, for instance — may have been too much to ignore. While privilege and fame can serve as an inspiration for the masses, it can also ignite resentment. At the end of the day, Beijing will do what it must to preserve order. Emerging from detention in October, Bingbing offered only a canned statement of self-criticism to her 63 million Weibo followers before falling into a conspicuous silence. She was issued a fine of 884 million RMB (roughly $127 million) and given an undisclosed deadline to pay up — a stark warning to others who would flaunt China’s routinely skirted tax laws.

“I heard a lot of star entertainers are busy paying their back taxes,” Zhou, the Beijing film critic, told me. “Or taxes they thought they had been exempted from.”

Reached via email, a former employee of Fan’s Studio confirmed that Bingbing’s manager Timothy Mou, who was arrested for allegedly attempting to destroy evidence during the tax investigation, has entered the judicial process. “He has some problems in this situation,” the employee wrote, using a phrasing that’s less ambiguous than it sounds: Chinese courts deliver a guilty verdict 99% of the time.

Beijing is not West LA, and a Chinese actress, no matter how many times she poses for photos with Will Smith or Jessica Chastain, is still beholden to the Communist Party.

I wish I could say that Fan Bingbing was an activist artist whose persecution at the hands of China’s authoritarian regime was retribution for speaking truth to power. I can’t. Bingbing is a very talented performer, but she is not a dissident like the artist Ai Weiwei, for instance, who was arrested, beaten, and ultimately exiled for his criticisms. Her creative output was almost always in lockstep with the Party’s vision — the kind of glossy period fluff that tends to please audiences and regulators alike — and her loyalty to her country was undisputed. Even her designs on Hollywood were more about extending the Chinese influence (and earning potential) than a bid for international prestige.

Still, when I read Bingbing’s initial public statement, after being released from custody in October, I couldn’t help but wince.

“For a long period of time, I did not uphold the responsibility of safeguarding the interests of my country and our society against my personal interests,” she confessed, adding, “Without the great policies of the Party and the country, without the love of the people, there would be no Fan Bingbing.”

At

first, I found it hard to reconcile this forced apology with the sarcastic, fun-loving woman I used to know. But beneath the layers of self-criticism, I saw the mournful defeat of an artist whose patrons had turned on her.

At

first, I found it hard to reconcile this forced apology with the sarcastic, fun-loving woman I used to know. But beneath the layers of self-criticism, I saw the mournful defeat of an artist whose patrons had turned on her.

It’s tempting to see her story as a parable of the changes that have taken place in China since 2008. Gone are the freewheeling days of fast cash and low accountability, when wayward foreigners like me could slip under the radar, or megacelebrities, like Fan Bingbing, could fly high above it. President Xi Jinping has made it clear — via parallel crackdowns on financial and social corruption — that his tolerance for the excesses of capitalism is much thinner than his predecessor’s. Unfortunately for Bingbing, in the words of a well-known Chinese proverb, sometimes you have to kill a chicken to scare the monkeys. The assumption now, among most people I talked to, is she won’t be allowed to work again anytime soon.

Then again, not everyone sees it that way , and the case may well be that Fan’s 2018 ordeal was nothing more than a road bump in her inevitable rise to global stardom. On April 22, Bingbing showed up at a gala for the Beijing internet streaming company iQiyi. It was her first public appearance in nearly a year, but photos from the event show the actress back at home on the red carpet, sporting Alexander McQueen and clutching a $5,000 Louis Vuitton Petite Malle — a sure sign that her endorsement deal with the French fashion house is still very much in effect.

If the tax scandal had negatively impacted her reputation in China, Bingbing’s international image seems to have been unaffected. New reports indicate that production has finally begun on 355 , a Hollywood spy thriller announced shortly before Bingbing’s arrest and co-starring Lupita Nyong’o, Penelope Cruz, and Jessica Chastain.

“Bingbing is in a good condition now,” a source close to the actress in Beijing told me recently. “She just needs some rest and adjustment for a while.”