Kaeso Lepidus pulled his rough woollen cloak tighter over his shoulders as he stirred the bean stew which was bubbling nicely over the open fire. Little snow flurries danced in the campfire light indicating winter’s approach and yet another hardship that must be endured. Lepidus was a military engineer, an Immune of the Roman VI Victrix Legion . He was one of the specialists of the Roman army. His rank, “ Immune ”, showed that he was literally immune from all other duties, including fatigues, training and even combat unless times were really desperate. The year was 122 AD and his task was to survey a route for a continuous curtain barrier across the entire breadth of Britanniae, a country what would later be known as England.

After nine weeks Lepidus had reached the middle section of the Island. The craggy hillocks will prove difficult for the following wagons of great stone blocks, and in some places wheeled transport will be impossible to negotiate and the rocks will have to be man-handled on wooden sleds up the very steep hills. Fortunately, such hard labour was not his concern, but he already had enough to deal with as it was. The Roman survey party had started out with a protection detail of 85 legionnaires. Yet the savage Picts who inhabited this wild country had already dispatched four careless Roman soldiers to their version of Valhalla. Each death resulted from a perfect ambush, and one of them occurred when the poor man was squatting at his latrine. In the daylight hours the enemy could sometimes be glimpsed in the far hazy distance in small groups as they paralleled the Roman survey party.

The Pict warriors were always observed at a distance, keeping close to woodland for the protection offered from Roman cavalry. But at night, the enemy came close. They came close enough for the Romans to hear their soft weird chatter and sometimes even close enough to smell their foulness, provided they approached from the West with the prevailing breeze. The Roman soldiers knew that every Pict spear point carried sudden death so were anxious throughout the long, cold night.

It took my wife and I two attempts to walk Hadrian’s Wall.

When it comes to organising overseas travel, my wife, Annie, is the guru. She spends almost a year planning, investigating, booking accommodation, buying tickets and arranging things to do and see. A long distance walk in a foreign country takes particular consideration. Ordinary things like which shoes to take involve precise judgements. If you commit to footwear on a walk of 130 km you better choose the best shoes right from the outset. When you are in the rural “middle” of the North of England there are no shoe shops, in fact there are hardly any shops at all. Then there is rain-gear, hats, sunburn cream, snacks and all sorts of bits and pieces to lug. The majority of your kit must be packed at home, which in our case, was 16,500 km away from Hadrian’s Wall. Lastly, whatever you choose to bring on the walk you must carry on your back so you choose wisely or you will suffer the consequences.

Of course, it is not necessary to carry everything you travel with on your back. My clever wife engaged a porter company who would pick up our heavy suitcases which contained all the necessities of life for a month in Europe and carry that excess luggage to our destination. So, we would leave our heavy luggage by the door as we set off each morning and we would happily find our suitcases magically awaiting us on our arrival at our temporary accommodation each night. All we would carry on our backs were the necessities to get us through each day’s walk. If anyone is contemplating a Hadrian’s Wall walk, I heartily recommend a porter service.

In 2014, we prepared for a month in Europe with a week to be spent walking the great Roman wall in the North of England. All preparations and planning had been complete and we were raring to go on our little adventure. Alas, at almost the last moment a little personal disaster struck. My wife tore her Anterior Cruciate Ligament (ACL) when dancing a few months before we were due to depart for England. This necessitated surgery, recovery and a great deal of practical care and physiotherapy for her damaged knee. We were both so looking forward to walking the wall that it was such a great disappointment. Plus, we had already booked and paid for accommodation and portage fees. What to do?

Rather than spend time, effort and mental anguish trying to erase all that planning and consuming time on money recovery, we decided that instead of walking Hadrian’s Wall we would drive it . So, keeping all the original bookings, we hired a car at Newcastle and drove hither and yon exploring every part of the existing wall and all the neighbouring hinterlands. In the long run, my wife’s ACL injury was beneficial because not all the Roman forts supporting the wall are actually nearby to it. We were able to explore just about all the forts that are located some distance from the wall itself by car. Three years later, when we did manage to walk the wall, we were able to concentrate on the great walk itself. We can say that we had the entire experience and one not available to most walkers, particularly those who have travelled from far distant countries.

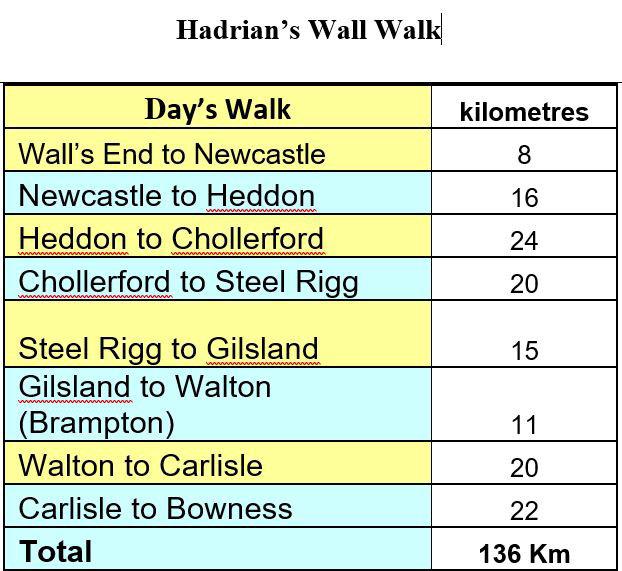

In the planning stage one must consider the first question: do you travel East to West or the other way round, from the Irish Sea towards Newcastle. The wall is bounded by Bowness-on-Solway in the West and Wallsend near Newcastle in the East. Annie and I decided to start in the East at the Newcastle end. We did this both in 2014 for the driving holiday and in 2017 for the successful walk. If we ever decide to walk Hadrian’s Wall again, which is a near certainty because we enjoyed the experience so much, we will definitely walk from West to East for one particular reason. The prevailing breeze for the entire walk is from the West. We knew this from the start and assumed that it would be pleasant and refreshing to be walking into a gentle breeze. And this was the case for the first day or so walking through into urban Newcastle and out through its suburbs. However, by day three this breeze and the repeated wind gusts to the face proved to be very annoying. Both of us decided that having these zephyrs pushing at our backpacks would be far more rewarding and less annoying than having that constant wind in our face. It’s a small thing, maybe, but on a long walk of over 130 km it is just one less annoyance to contend with.

It made good sense to spend the night in Newcastle, leaving our luggage at our accommodation, and catch the train the relatively short distance to Wallsend to begin our long walk. At Wallsend there is museum that explains all the different aspects of the great Roman wall and also contains the ruins of the first Fort at the mouth of the River Tyne. We explored the museum and the foundations of the fort, but in truth, we were eager to commence our foot journey. In typical couple fashion we marked the journey’s start by some stupid argument that I can no longer remember so the first couple of kilometres of our much-anticipated walk were done in silence. Because I am such a nice person, I forgave her for whatever trivial sin she must’ve committed at the start of the journey, and in short time were walking hand-in-hand along the path following the dirty brown river which is almost the entirety of the first section of the Hadrian’s Wall walk. At this point I should remark, in case there was any confusion, the great Roman Wall only exists in patches nowadays. Possibly only about 15% of the wall is intact to any great extent. The greatest section of the existing wall lies in the middle bit and most of that is not much greater then waist high at best, although some parts are about head height. That is not to say that the wall is entirely absent at any point. Archaeologists have done a brilliant job of making the Hadrian’s Wall path follow the actual wall whether it is visible or not. They are aided by the Vallum which is a shallow trench which was dug along the entire south side of the wall, the purpose of which is not entirely clear, but was probably a defensive feature to protect the wall from the Roman side.

Confusingly, Vallum is Latin for “wall” and the Romans called the entire stone structure the “ Vallum Hadriani ” or Wall of Hadrian. Hadrian being one of the “good” Roman emperors who reigned from 117 to 138AD. Just about all the “good “Roman emperors came from the early period surrounding Emperor Hadrian. The nomination of “good” is due to some truly atrocious later Roman emperors, majority of whom never enjoyed a natural death. As an example, in the year 193 AD, a total of five claimants for the title of Roman Emperor briefly reigned: Pertinax, Didius Julianus, Pescennius Niger, Clodius Albinus, and Septimius Severus.

Emperor Hadrian ordered the structure to be built in 122 A.D. but the reasons for its creation are obscure and much argued about. Having walked the damn thing for a week I have a few ideas of my own which I will pontificate about later on. I won’t turn this story into a day-by-day journey because I’d rather discuss the walk as a whole and the feelings that were invoked by the long walk. I also want to talk about wall itself because the great Roman wall is really the star of the show.

Let us start with a basic description of the wall as it was about 130 A.D.

The great wall was 80 Roman miles from end to end, (73 modern miles) or 117.5 km. Every Roman mile along the wall there was a milecastle, and in between every milecastle there were two turrets. Every five Roman miles there was fully defensible military fort to the rear of the wall itself, containing either infantry or cavalry — there were between 14 and 17 of these forts and each held between 500 and 1000 men. In front of the wall, at about 10 miles distance from it on the “barbarian” side there were four additional forts. As you can see, the wall in its entirety was no simple barrier. Every element was essential and consisted of interlocking defences that were extremely complex.

The wall itself was made up of squared or dressed stone and measured 3 metres (10 feet) wide and 5 to 6 metres (16 to 20 feet) high. There are many academic arguments about whether the wall would have contained a walkway on top. Why there wouldn’t be a walkway is a mystery to me because it would be the quickest way of reaching the turrets that lay a third way along between the milecastles. In addition, it’s easier to patrol from a height by one or two people than any other method that I can imagine.

Immediately in front of the wall, there was a deep “V” shaped ditch filled with brambles and thorn bush — which acted as an ancient form of a barbed wire obstacle. Then came the great wall itself, and after that a service road along the friendly side of the wall to allow movement of men and supplies. On the other side of the road on the southern side they dug a deep ditch, or v allum, which had a built-up mound on each side. Nowadays the only thing that can be seen for most of the Hadrian Wall walk is the shallow depression of the great vallum . After 2000 years, Roman Britain is still represented by this ditch which was dug along the entire length of the Tyne–Solway Firth isthmus — or the waist of Great Britain.

To see the thing from the perspective of an attacking barbarian Pict, he would have to, somehow, get past the military forts a full 10 miles north of the wall without being observed . These forts were bases for intelligence collection. Not only were they heavily manned, infantry, and especially cavalry patrols would be continually intersecting from forward base to forward base, and also deep into enemy territory further north.

The Roman cavalry patrols would completely dominate the Scottish Lowlands. This was Hadrian’s Wall’s first line of defence, 10 miles north of the stone barrier. So, if an attacking Scottish force managed to get past the forward Roman bases, and they, somehow, evaded the many cavalry patrols, and somehow reached the wall itself, that’s when new problems will arise.

The Pict commander would be looking over a wide and deep ditch full of thorn bushes, and contemplate a 20-foot-high stone wall on the other side of that initial obstacle. And, as soon as they were detected by the Roman garrison along the wall, they would see a string of signal beacons suddenly light up along each side of the wall to the East and to the West. Each light blinking an alarm and call to arms. Within minutes heavily armed soldiers would be gathering their weapons in the forts to either side of the threatened section and preparing to ride to the defence of the wall. Infantryman would also set out and cover the 5 miles in about an hour, with the cavalry arriving in just a fraction of that time. The small garrison at the wall itself would be inflicting a terrible punishment on any Scottish attempt to clamber over the wall. The Roman soldiers who garrisoned the wall were not frontline legionnaires. These men were considered auxiliaries, recruits from all over the Empire, including Germans, Belgians, Franks, Egyptians and Syrians. However, they spent a minimum of two hours a day training for combat. Some of them could hit a playing card at 40 feet with the spear. Any Pict contemplating attacking the wall over a ditch would have a hard time of it. All the while troops from the forts behind the wall would be sallying out from the gates on either side of the Picts completely surrounding them. For Roman soldiers fought on open ground and the wall’s primary purpose was to delay and contain an attack for a pending mass assault from the flanks.

The ancient records concerning the military use and reasons for Hadrian’s Wall are scanty to say the least. Historians have, as historians do, attempted to fill the gaps by looking at the times as they were, the function of the Roman legions, and the remaining evidence that the wall presents. Some of the theories I find are plainly wrong. I should say that I am not a professional historian, nor am I an expert on Roman military history. I am however a former soldier and have experience in building defences in relation to the lay of the land and the likely threat. It doesn’t make me right, but it does make me wonder.

One of the theories is that the wall was built primarily to coordinate tax collection and defeat tax evasion. It certainly could do that very well. It would be impossible to get a herd of cattle through to either side of the wall without going through a Roman taxation portal. I have no argument that the wall fits that purpose exceedingly well. But when you look at the extraordinary expense of Hadrian’s Wall - three legions consisting 15,000 men building a barrier across the entire breadth of England when every other frontier taxation was maintained by patrols you have to wonder what made the North of England different. Secondly, 20 years after its creation, Hadrian’s Wall was abandoned and another wall created hundred miles further north. In the years after Hadrian’s death in 138, the new emperor, Antoninus Pius, left the wall occupied in a support role, essentially abandoning it. He built a new wall, this time made of cut turf 40 Roman miles in length. This wall only lasted 20 more years before it was abandoned in turn. It seems that the Scottish people proved more troublesome the further north their land was occupied. So, the Romans returned to the original wall just inside what is now the North of England and they remained there for almost three centuries. To my mind there could be no doubt that Hadrian’s Wall was built as a barrier in the middle of extremely hostile territory. Secondly the sheer complexity of the military defences and its interlocking systems was a result of never-ending danger. This was no mere taxation gate, this was a serious and life-threatening situation. The Scots meant business and the Roman defences were countering a real threat. In some of the forts in the middle section of the wall, the Romans even had their baths constructed inside the military forts, which was counter to the usual practice. Normally every fort had such facilities built outside the military boundary. Also, there is a great deal of vague ancient writings concerning many hostile clashes with the Pict tribes. Modern historians have tended to discount most of these sources as exaggerations because the idea that naked spear welding barbarians could be a real threat to the highly organised and highly efficient Roman armies was preposterous. One recorded event described a major war which took place shortly after AD 180, when ‘the tribes crossed the Wall which divided them from the Roman forts and killed a general and the troops he had with him ’.

Another theory had it that the great wall was merely a shining device to reflect the power and glory that was Rome. To me this is the most ridiculous story I have ever encountered. Particularly that even now the great majority of where the wall runs is largely sparse and deserted. The idea that the Romans expended so much treasure and men simply to impress a few barbarians doesn’t bear serious consideration.

It is said by some that a wall walk departing from Newcastle can be a tad boring. We never found it so. It is true that a walk along urban development is not particularly exciting but we were well into the spirit of the journey and crossing highways and strolling through suburbia was part of it. All too soon we were in the countryside where the real adventure for us began. For the most part the wall is non-existent here as it is really non-existent for the majority of the walk. That said, here and there a section of 50 or 100 metres would suddenly emerge out of the meadow for no particular reason that we could discern.

If the wall is largely non-existent now, where did it go? After the Romans departed Britain in 410 A.D. Hadrian’s Wall was left to crumble. It became, in effect, the world’s largest quarry. Over the next 15 centuries whoever wanted free cut and dressed stone could simply roll up to the wall and help themselves. As we walked along where the wall used to be, we would pass through towns where the local churches, manor houses, civic buildings and boundaries were all made up from stones liberated from the Roman wall. Much of the wall, perhaps the greatest part, was removed during later construction of the adjacent “Military Road”. General George Wade began construction of the road in 1746, in the wake of the Jacobite risings, in which Bonnie Prince Charlie had evaded his forces in Newcastle and been able to attack Carlisle in the west.

In light of this, an all-weather road was considered a matter of urgency, as Wade was anxious to move troops from Newcastle to Dumfriesshire and there was no route suitable for troop movements. Much of the material from Hadrian’s wall (primarily limestone and sandstone) was salvaged and used for hardcore in its construction.

Once in the countryside, a walker will experience the near surreal enjoyment of walking in some of the most beautiful countryside in all of England. It is just one sweet and green meadow after another walking alongside the friendly, shallow vallum. Every so often the bones of one of the many forts or milecastles or pop into view, only to fade away again into the grass as a path continues westward. Each meadow is bounded by fences, whether the meadow is 100 metres wide or a kilometre, the walker will still have to do clamber over a stile to get to the next field. In total you have to clamber up and over several dozens of these stiles, and I always thought that I would get sick of doing so, but we never did. They were just part and parcel of the overall experience. We also marvelled at the ingenuity of the English farmer at providing so many different ways of being able to climb over a fence without presenting much effort in doing so.

After a couple of days the walker will hit the crags. Any walker worth their salt would be expecting this wild countryside after completing research on the walk. But it was still breathtaking to experience it in the flesh. This is where the heavy climbing begins, up and down endless rolling hills. Some can be truly exhausting but also truly exhilarating. For it is this section of the walk where Hadrian’s Wall bursts out of the ground, emerges from its hidden foundations after all these miles and really makes its presence felt.

As far as the eye can see you will view long ribbons of the Roman wall. You can touch with your hands stones that were set in place by one of three legions — by one of 15,000 men who built the thing. The wall becomes an alive object at this place. Details jump at you. You can stand in the foundations of a milecastle and see in the stone at your feet a hole drilled into the living rock that once contained a bolt that held a door in place to keep out the weather. Stepping back away from the wall you can see where the kitchens were that fed the garrisons which rotated through the encampment. At this point the wall ceases to be a historical artifact and instead becomes alive with soldiers stamping their feet at the cold, or arguing over a game of dice. It is impossible not to have several kilometres of wall on either side of you and not see it as it was in 130 A.D.

The garrisons who manned the wall were from far-flung countries. They were not frontline troops, nor even Italians, they fought for Rome but were not Roman. Virtually none of these ‘Roman’ soldiers had ever been to Rome, and nor would they ever visit the place. Roman legionnaires signed on for 25 years, and if they performed a faithful service during their time in the military, they would become Roman citizens and be given a plot of good farmland. However, being a Roman citizen didn’t mean that they would go to Rome, or even afford to travel there. Rome was a state of being, it was an idea, a vision of what could be, what should be. It came to pass in much later eons of the Roman Empire that not even Roman emperors had much time for Rome itself. In that later period, it was the frontiers such as Great Britain, Africa and Germany where Rome was governed. And perhaps one of the greatest Roman emperors who ever lived, Constantine, declined to live there moving his throne to Constantinople in 330 A.D. Yet for three centuries soldiers manned this cold stone barrier; soldiers who would struggle with the Latin language all their lives, and defended the outer limits of what they believed to be Western civilisation in Rome’s name.

At the end of two and a half decades, if they performed their service well, these foreign troops would, at last, become citizens of the citystate of which they only had vaguest notion. At that point, most of them would take off their light armour, hand in their gladius, or short military sword, and become a Roman citizen. The majority would then have taken a plot of land close by to the very wall that they had defended for all their adult life. They would marry a local girl, farm the rich soil and settle down for their remaining years. And when they weren’t involved in the heavy manual labour of the farming seasons, they would, perhaps, sometimes wander down to the little settlements that had sprung up to service the military encampments along the wall. More than likely they would search out a warm tavern as was their only comfort during their long years of service as a legionnaire. Once comfortably ensconced on a rough wooden seat, they would drink with the other old soldiers, and also perhaps with the young Roman warriors newly arrived.

Over many an ale they would tell lies about their own service on the great Roman wall and they might show the scars where some Pictish arrow-point had pierced their flesh.

They were now full Roman citizens, far from the land of their birth and at last they had arrived.